The U.S. Civil War is considered the first war of the industrial era. The conflict was supported by innovations like the telegraph, railroads with armored trains, and ironclad ships. Firearms were now rifled, machine guns had appeared, and soldiers dug into trenches. Yet, more conservative generals still preferred colorful uniforms and tight formations. This combination of new technology and outdated tactics led to incredible casualties. Around 750,000 soldiers died, along with an unknown number of civilians. In fact, the U.S. lost fewer lives in all subsequent wars combined than in this conflict.

Reconnaissance Balloons

Although airplanes were still 40 years away, both the Union and Confederacy experimented with aviation using reconnaissance balloons. These handcrafted balloons were given names such as Intrepid, Union, and Gazelle. The Gazelle lived up to its name, being used the most frequently and setting records for miles traveled. The balloons were lifted to heights of 250-300 meters, from which crews observed enemy movements and the progress of battles. Since radio communication didn’t exist yet, signals were sent down using special flags. The telegraph was used much less often, but when it was, it must have been an impressive sight. Although the balloons were never used in direct combat, some innovators proposed bombing from them. Regardless, this marked a significant advancement in battlefield reconnaissance and coordination.

Submarine

The concept of submarines already existed, and some early prototypes were built. In 1863, entrepreneur Horace Hunley funded the construction of the H.L. Hunley, the first Confederate war submarine. However, its trials ended in disaster — twice. On August 12, 1863, the submarine sank, killing five crew members. Two months later, it sank again, this time taking eight lives, including Horace Hunley himself. Despite these setbacks, testing continued. On February 17, 1864, the Hunley went on its first mission, targeting the Housatonic, a Union ship blockading the Confederate-controlled city of Charleston. The attack was successful — the single torpedo sent the ship to the bottom. However, the Hunley also sank. The explosion was so strong that it affected the submarine itself. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that the Hunley was recovered from the harbor floor. All eight crew members were found in their stations. Experts concluded that a failure in the oxygen system led to their deaths. Today, the H.L. Hunley is restored and displayed in a Charleston museum.

The First Dollar

After gaining independence, the national currency of the U.S. remained the Spanish peso, although the notes were already being referred to as dollars. Soon, the U.S. began minting its own one-dollar coins, which could be made of copper, silver, or gold. The period from 1837 to 1866 is known as the “Free Banking Era,” and the term should be taken literally. During this time, over 8,000 types of banknotes were issued by states, banks, railroad and postal companies, and sometimes even churches and private individuals. The financial chaos intersected with the military chaos, leading to a more organized system. In July 1861, Abraham Lincoln authorized the U.S. Treasury to print paper money. At the time, many saw this as a departure from the ideals of the Founding Fathers. America was supposed to be a land of absolute freedom from government control, and even the existence of banks was criticized by conservatives. Nevertheless, the first true green-colored dollars were printed during the Civil War. The public was promised that these “greenbacks” could be exchanged for gold later, once the war was over. Obviously, that promise has never been fulfilled. By 1865, about a third of all U.S. paper dollars were counterfeit, prompting the creation of the Secret Service to combat counterfeiting, which gradually gained more responsibilities.

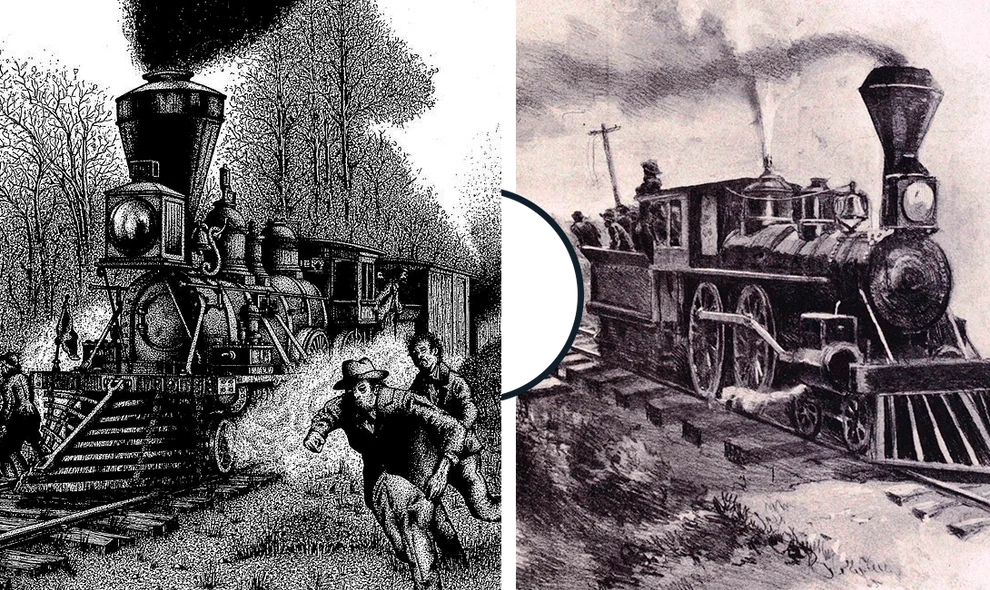

The Great Locomotive Chase

On April 12, 1862, a group of Union Army volunteers hijacked the Confederate locomotive General. The train headed north toward Union territory but made frequent stops. The main goal of the raid was to completely disrupt the South’s logistical infrastructure. Telegraph wires were cut, dynamite was placed under the tracks, and even small stations and platforms were destroyed. The Southern army was already struggling with moving troops, heavy weapons, and supplies, and the audacious raid was a blow they couldn’t ignore. Confederate railroad workers couldn’t send a message about the hijacking to the next station because the telegraph stopped working as soon as the train arrived. At first, they pursued the locomotive on foot and then used surviving handcars. Eventually, another locomotive, Texas, joined the chase. The pursuit covered 140 kilometers before the Union raiders ran out of fuel and had to abandon the General, fleeing into the nearby woods. Many of the raiders managed to return to Union territory, but their leader, James Andrews, was captured and sentenced to be hanged.

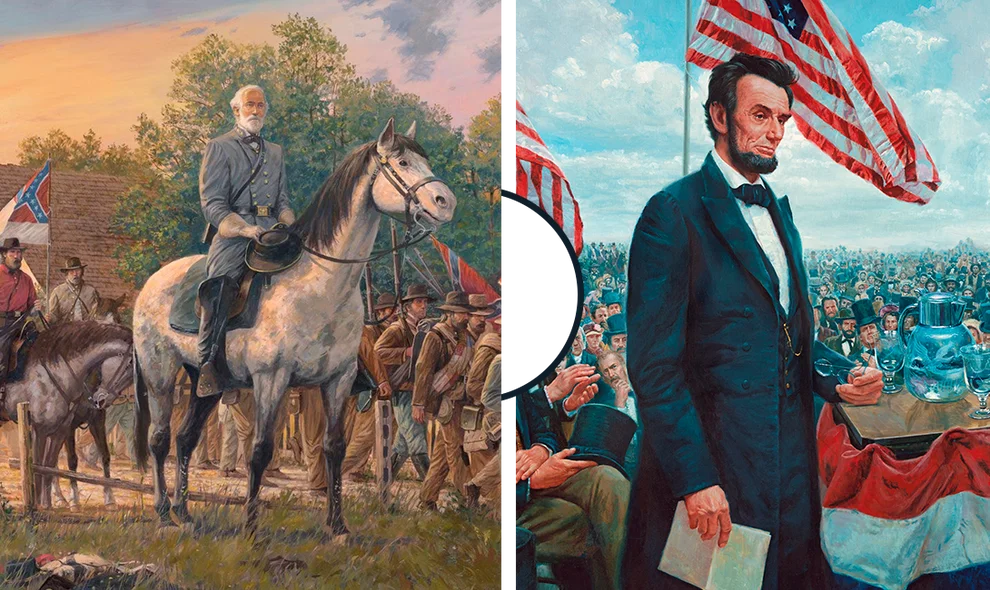

The Worst Day

There are no good days in war, but some are especially bad. For Americans, that day was September 17, 1862. Near the town of Sharpsburg, along Antietam Creek, two armies lined up. The Union forces were commanded by George McClellan, and the Confederacy was led by General Robert E. Lee. The Union had nearly twice the number of troops and many rifled muskets, whose significance was underestimated, especially in open-field battles. Nevertheless, Robert E. Lee cemented his status as one of America’s most talented generals. The Confederates chose the most advantageous positions for their lightning counterattacks. Both sides suffered roughly equal losses, with 3,700 killed and over 17,000 wounded in total. Never before or since has the U.S. experienced such heavy losses in a single day. Technically, the Union won by stopping the Confederate advance on Washington. This battle was pivotal, as Robert E. Lee’s defeat forced France and Britain to reconsider their stance. The seemingly invincible Confederacy was revealed to be not so formidable. European sympathies shifted towards Abraham Lincoln, and talks of officially recognizing the Confederate States of America ceased forever.