110 years ago, in December 1914, the Christmas Truce took place: soldiers of the First World War temporarily laid down their arms to celebrate the old Christian holiday together. This practice began to spread along the fronts, and not solely out of humanitarian reasons. “Front-line camaraderie” started being utilized for military purposes as well.

A Stalemate

The First World War began as a maneuverable conflict, but a few months later, operations intended to achieve resounding victories concluded without either side reaching their goals. In attempting to outmaneuver each other, they encountered various geographical obstacles and came to a halt. By the end of 1914, the fronts had solidified. Defensive lines were continuously improved, reinforced, and deepened. This entrenchment created a significant positional stalemate. Neither opponent could break through the front without immense resource expenditure — suffering losses in the hundreds of thousands and expending millions of shells. Even when such breakthroughs were achieved, the success often held little strategic value.

The First World War saw the use of almost all the technical innovations that would later prove effective in the Second World War, including tanks and aircraft. However, neither side had yet developed and implemented effective strategies for their use. There were no maneuverable units capable of both advancing successfully and defending steadfastly while moving quickly. The very units that could break through fortifications and create encirclements, as seen in the Second World War, were lacking. Without these capabilities, winning the war was only possible through attrition, which was psychologically grueling. It’s one thing to chase a retreating enemy, gaining momentum and visibly seeing the impact of one’s successes on the front lines. It’s quite another to endlessly sit across from each other in the same trenches, in all weather conditions—cold, mud, frost, or scorching heat.

All of this was compounded by the constant fear that a shell could come from beyond the horizon at any moment, killing you before you even had a chance to retaliate. The sense of futility and helplessness, exacerbated by harsh living conditions, eroded discipline and damaged an equally crucial component for a soldier — the will to kill the enemy.

Christmas Miracle

In the summer of 1914, when the war had just begun, the peoples of the great European powers welcomed it with enthusiasm. Patriotic demonstrations erupted in the capitals. Everyone believed in the victory of their country and thought the conflict would be short-lived. Most soldiers heading to the front seriously expected to be home by Christmas.

Then Christmas arrived, and there was no sign of returning home. Realizing that their beloved holiday would have to be spent in the trenches, the soldiers were disheartened. But the Christmas spirit indeed could work miracles — even in such a dreadful place. From time to time, in any positional war, the sides would arrange truces for sanitary purposes: these were necessary to remove the dead from no-man’s land. In December 1914, such truces on the Western Front coincided with Catholic Christmas. Soldiers had previously exchanged a few words with the enemy during these moments. But now there was a reason to communicate more closely. Some had stored up alcohol, and others had snacks. After all, it was a truce and Christmas! Eventually, soldiers began to cautiously, then more boldly, venture into no-man’s land in groups to chat, drink, and eat together. Conversations led to joint festivities.

In some places, friendly relations began after the joint singing of Christmas carols. The first lines of trenches in some areas were separated by mere tens of meters, so both sides could hear each other perfectly. Soon, the space between the trenches — a deadly zone! — turned into the strangest Christmas festival in the world. Sometimes someone in the trenches had a football, and the enemies played matches, managing to hold several games. There were no “guest” and “home” teams—everyone played wherever they could find a flat enough spot on the shell-cratered no-man’s land. Some might naturally wonder: why? Why did the enemies take this step? Did they trust each other that much?

Part of the reasons we’ve already mentioned. The people in the trenches were exhausted and weakened. It also mattered that the soldiers on both sides — mainly white Christians — were quite similar to each other in appearance and cultural traits. Additionally, most losses in the First World War were caused by artillery; in other words, it was usually something invisible that killed, coming from beyond the horizon. Those sitting in the front-line trenches felt a sense of camaraderie: both sides served as a sort of living shield, necessary for the artillerymen to reap their harvest. In such a situation, infantrymen hated each other much less than they might have. Everything eventually ends. But that time, only Christmas ended, followed by the year 1914.

Trench Life Realities

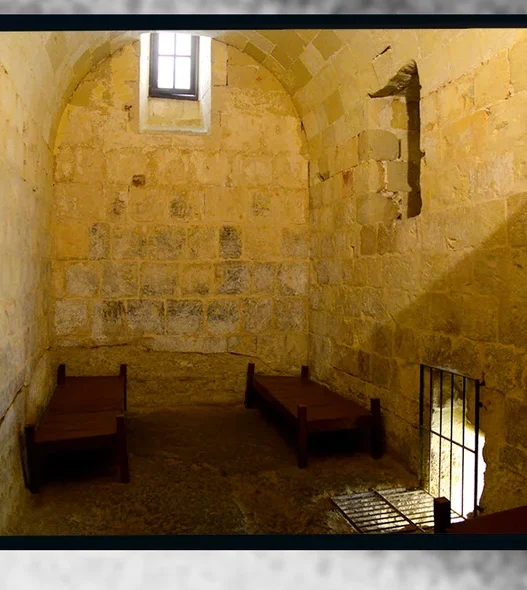

Life in the trenches of the First World War was crowded. On the front line, it was impossible to arrange proper bathing facilities, and as a result, lice infested everywhere and everyone. Even if they were diligently picked off clothes, they would return within a few days. Lice bites were incredibly irritating, especially at first. But the main problem wasn’t the bites, which soldiers eventually got used to. The issue was that lice spread diseases and caused epidemics. There were other unwanted guests as well. Rats always followed large gatherings of people: where there was fodder, there was always something for them to eat. And in no-man’s land, the rats feasted on corpses. However, they preferred to live in warm dugouts. Eventually, the rat situation became so dire that they began running over the faces of sleeping soldiers as if it were a parquet floor. Then, cats were brought in, and where they couldn’t cope, terriers—dogs bred to fight rats — were used. While cats often played with their prey, terriers fiercely and efficiently killed one rat after another.

Reconnaissance by Combat, Reconnaissance by Peace

The Christmas miracle provided the adversaries with more than just a day of peace. “Fraternization” became an unpublicized but constant companion of the First World War. Later, using the relationships established during these truces, soldiers mimicked activity with minimal risk to themselves. Even scouts, who were sent on dangerous raids into enemy trenches, would visit the enemy at pre-arranged times, exchange cigarettes, chat, and then return. However, they were not always successful in hiding this. Sometimes the command would discover these activities, punish those involved, and write angry reports — otherwise, we wouldn’t know about these incidents. Fraternization was a kind of relief for soldiers trapped in the positional warfare of WWI. The harsh conditions of the war left little room to blame them. However, in war, the soldiers’ objective is to destroy the enemy and allow their country to achieve victory on its terms. That’s why the command always tried to suppress fraternization — it was a powerful blow to discipline. If left unchecked, the troops would eventually become uncontrollable, turning into an armed mob. Such a mob, for example, literally tore apart the acting Supreme Commander-in-Chief, General Dukhonin, in 1917, and, in a broader sense, the Russian Empire itself. The First World War ended with massive soldiers’ mutinies. Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, the Ottoman Empire — all these countries experienced revolutionary events. Unable to break through the enemy’s defense, the warring sides resorted to a war of attrition. The loser was the one who broke first, not the one who avoided sweat, blood, tears, and suffering. The example of Russia and its massive losses in the Civil War demonstrated that such a defeat leads to far greater casualties than the war itself. Therefore, a tough approach to combating fraternization made sense.

The most effective method was the rotation of units. “Good” relations between adversaries developed when the same people faced each other, and neither side showed much activity. When personnel changed, establishing interaction became more difficult. However, this method had a serious drawback: the newcomers were less familiar with the terrain. Knowing the terrain well in positional warfare is very important. A new bump in the ordinary landscape could well be a death-dealing artillery observer.

Another option was to catch fraternizing participants on the front and hit the enemy with artillery fire when they moved toward no-man’s land. This usually provoked fierce resentment: “We came out of the trenches, and they…” It was also possible to rake with machine-gun fire — but this had to be done personally by a junior officer or sergeant. This was a person with enough authority not to become the target of soldiers’ revenge for breaking the “agreement.”

Such authority was gained, for example, by participating in trench raids. After long observation, the military would choose the most relaxed section of the enemy trenches, and then, most often at night or at dawn, when the sentries were most tired, a storm group would burst in. In the ensuing battle, using the element of surprise and the enemy’s shock, the soldiers would destroy the enemy infantry in the trenches and quickly retreat to avoid a counterattack. If the operation was well planned and executed, the soldiers would gain trophies — from personal items to weapons. Sometimes they captured a prisoner to gather more intelligence about the enemy. But the most valuable reward was the combat spirit and confidence — this best protected the troops from disintegration and endowed them with the determination to fight. Nothing boosts morale like one’s own successes and a sense of superiority over the enemy. This was how the prominent German writer Ernst Jünger spent his time — an anti-Remarque of his era. His book “Storm of Steel” (1920) is perhaps the best memoir of the First World War and one of the best war memoirs in general.

Death from Nowhere

In this prolonged war of attrition, artillery was responsible for the majority of casualties. It played the role of a hammer, delivering the strongest blows. The anvil was the endless lines of fortifications that prevented the enemy from breaking through to the artillery positions and capturing the guns, much like in the era of linear infantry. Artillery could have played a decisive role in breaking through defenses — a role it later assumed in World War II — but in the 1910s, imperfect communication hindered this. Once the infantry went on the attack and advanced far enough that the artillery lost sight of them, accurate fire with adjustments became impossible. Thus, much of the war remained a positional stalemate.

The Stage of Acceptance

As the conflict dragged on, maintaining discipline and combating fraternization among adversaries became increasingly difficult. This was an almost inevitable consequence of a war of attrition and, at the same time, an indirect sign of defeatism. The more soldiers sought to fraternize, the greater the risk of losing. This understanding led commanders to an intriguing idea: if the enemy wanted to befriend, it should be encouraged, not forbidden! The key was to ensure their own soldiers didn’t catch on to the idea. Hence, the most principled fighters were formed into special teams to fraternize with the enemy. They approached the enemy cheerfully, with snacks and alcohol, but in reality aimed to penetrate deep into enemy positions and gather intelligence on the state of the trenches, the quantity and quality of weapons, and, most importantly, the condition of the troops. For example, how demoralized they were — maybe dozens were ready to surrender right then. Perhaps the guard at that position was slack, making it vulnerable to a daring raid.

Fraternization became a political weapon for international revolutionaries, like the Bolsheviks. Initially, they exploited war fatigue to gain the soldiers’ support. After coming to power, they tried to use friendly relations against their enemies — the Germans. Trotsky, before signing the ill-fated Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, aimed to propagate as many German soldiers as possible during negotiations. The Germans understood the threat and included a ban on such actions in the preliminary conditions, which did not deter Trotsky. However, for every sword, there is a shield. On the other side, professional fraternizers were often met by counter-fraternizers! These would welcome them with open arms, alcohol, and food, engage them in conversation, and prevent them from going deeper to spy on or influence anything.

The story of the Christmas truce on the front is full of hope and the sense of a miracle. It showed that even in horrific conditions, exhausted and weary people could still be human. Unfortunately, such peace did not last long and did not lead to a global armistice. Moreover, the warm friendships that developed in the trenches between adversaries eventually became a weapon in themselves.