In the modern world, electricity is almost as familiar as air and water. The largest of human-made structures and the most everyday household appliances operate on electric current. It would not be an exaggeration to say that modern civilization exists thanks to electricity.

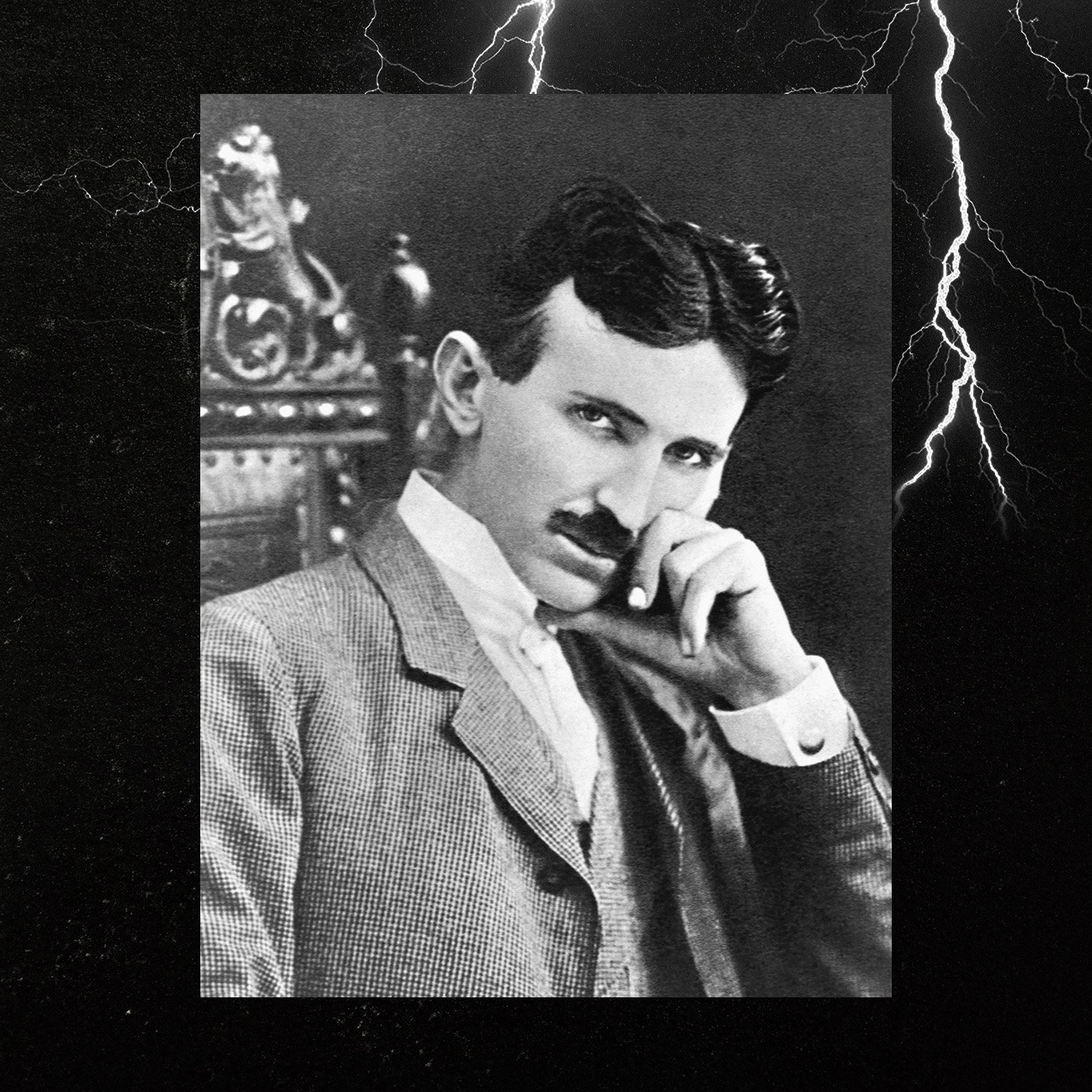

Today, few remember that the first serious studies of this phenomenon began only two or three centuries ago. Many great scientists worked to understand the phenomenon of charged particles and harness them for human service. Suffice it to mention the names: André-Marie Ampère, Michael Faraday, James Maxwell, Heinrich Hertz. Among these great names, Serbian scientist Nikola Tesla occupies a special place. Without his work, the world would not be what it is today.

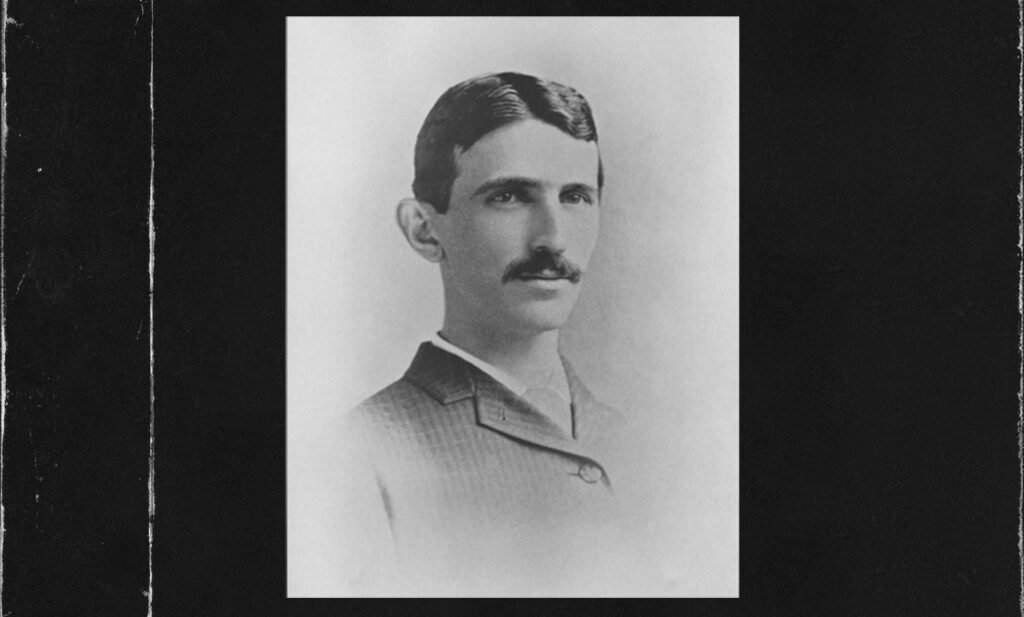

Tesla, who was ahead of his time in many ways, is called “the inventor of the 20th century.” However, there is an opinion that he “invented” the 21st century as well. His name is surrounded by an aura of mystery, and it is often difficult to separate truth from speculation. What was Nikola Tesla really like?

Chronology

1752 Benjamin Franklin observes electrical discharges during a thunderstorm.

1800 Alessandro Volta invents the artificial source of electric current.

1831 Michael Faraday discovers the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction.

1856 Birth of Nikola Tesla in Smiljan, Croatia.

1875 Tesla enters the Higher Technical School in Graz.

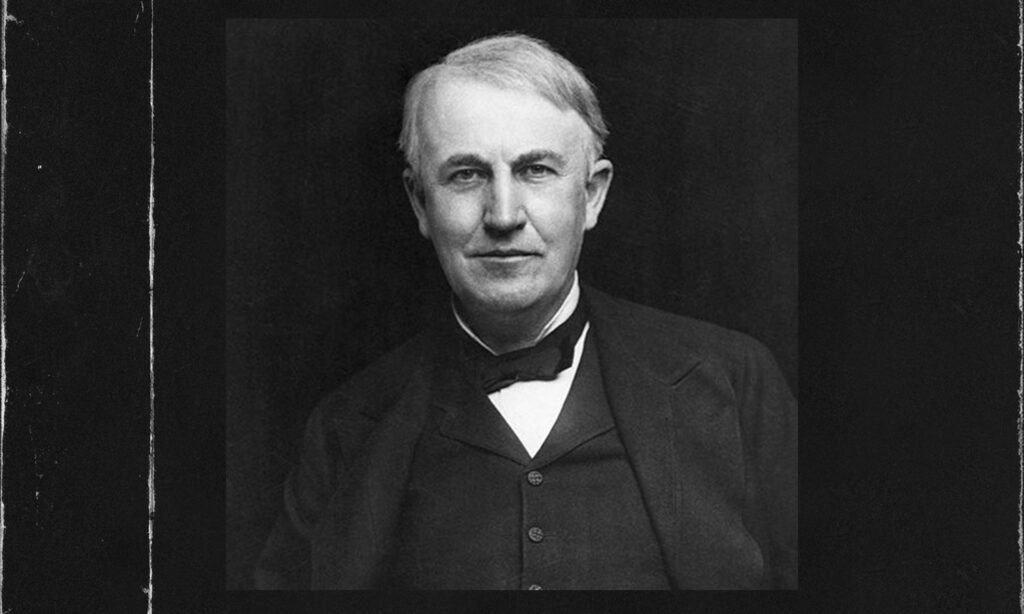

1880 Thomas Edison establishes the “Edison Illuminating Company” in New York. Tesla enrolls at the Faculty of Natural Philosophy at Charles University in Prague.

1884 Tesla arrives in New York and starts working for Edison’s company.

1886 Tesla establishes his own company, “Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing,” later taken over by investors.

1887 Tesla begins cooperation with the “Westinghouse Electric Manufacturing Company.” The “War of Currents” between Edison’s and Westinghouse’s enterprises.

1891 Tesla obtains American citizenship and establishes a laboratory in New York.

1892 Tesla is elected Vice President of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

1893 Tesla and Westinghouse create the lighting system for the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Start of work on the “Niagara Project.”

1894 Tesla demonstrates the first successful experiment in radio transmission.

1896 The Niagara Hydroelectric Power Station goes into operation, supplying electricity to the city of Buffalo.

1899 Tesla moves to Colorado Springs for extensive experiments.

1901 Construction of the Wardenclyffe Tower on Long Island, New York.

1909 Guglielmo Marconi receives the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the development of radio.

1915 Tesla unsuccessfully attempts to sue Marconi for patent infringement.

1916 Tesla is awarded the Edison Medal by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

1928 Tesla receives his last patent in his lifetime—for a vertical take-off aircraft.

1931 Time magazine publishes a portrait of Nikola Tesla on its cover.

1937 Tesla works on developing “death rays.”

1943 Death of Nikola Tesla in New York. The US Supreme Court recognizes Tesla’s priority in inventing the radio.

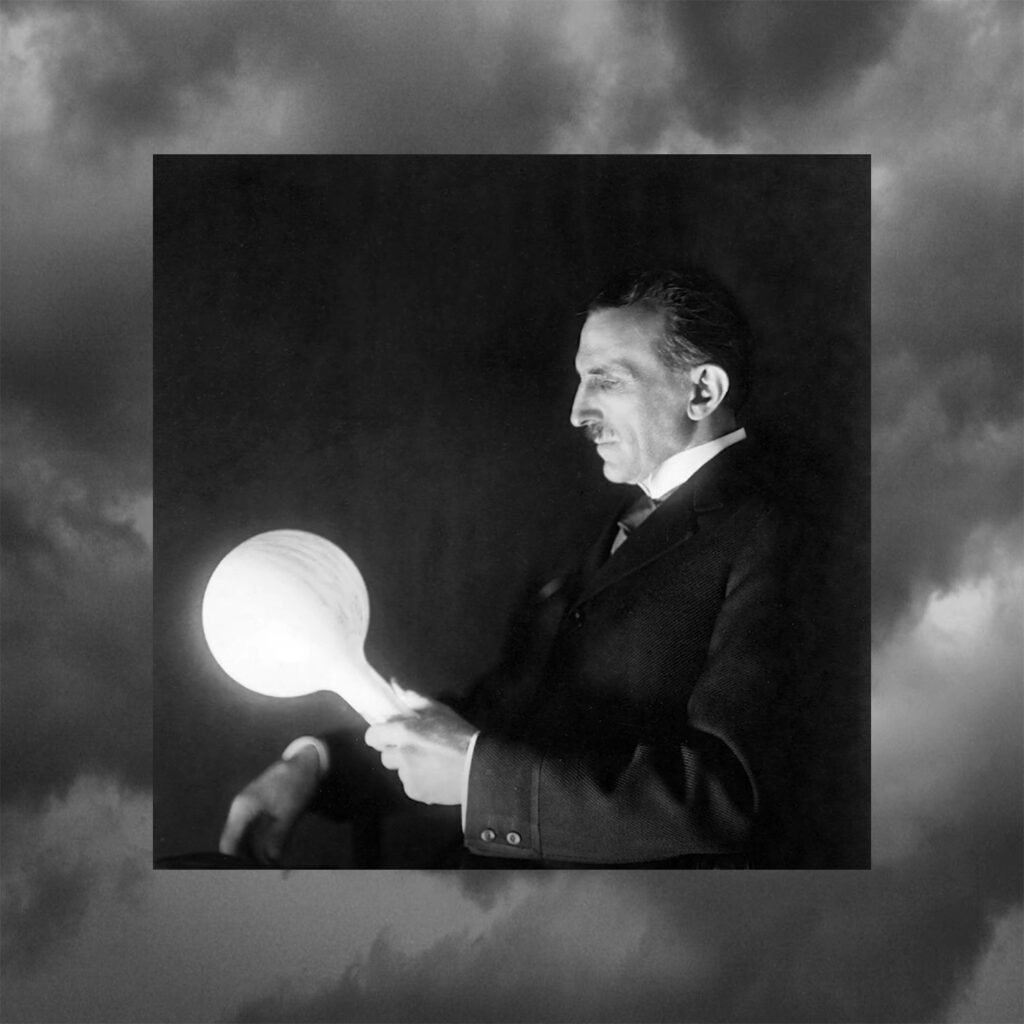

“The Electrical Wizard”

Bold experiments and projects during his lifetime earned Nikola Tesla the title of the “electrical wizard.” He truly stood out from others: possessing a photographic memory and some other unusual abilities. However, all of his “miracles” Nikola Tesla achieved solely due to his own talent and immense hard work.

Passion for Technology

In a Priest’s Family

Nikola Tesla was born on July 10, 1856, in the Croatian village of Smiljan, where his family—Serbs by nationality—had lived since the mid-18th century. From childhood, he absorbed both Croatian and Serbian traditions. The father of the future scientist, Milutin Tesla, was a priest of the Srem Diocese of the Serbian Orthodox Church and had received an excellent education: besides theology, he knew natural sciences, mathematics, literature, and several foreign languages. Intelligent and proficient with the pen, Milutin Tesla caught the eye of the priest’s daughter, Đuka Mandić, an extraordinary woman renowned in the district for her handicrafts.

In 1855, a year before Nikola’s birth, the Tesla family moved to Smiljan. Legend has it that a severe storm broke out on the day of his birth. Nikola Tesla’s childhood passed in an idyllic rural setting. He, his elder brother Dane, and sisters Milka, Angelina, and Marica loved to frolic in nature.

Quest for Knowledge

In 1861, a terrible tragedy struck the Tesla family. Dane, the elder brother of our hero and the darling of the entire family, fell off a horse and died from his injuries. The death of his brother greatly frightened Nikola. Dane was a very talented boy, and the future scientist, who was deeply attached to him, later recalled: “Compared to his talents, mine seemed like a pale imitation. And if I did anything worthwhile, my parents felt the loss even more deeply. So, I grew up feeling insecure.” Soon after, their father received a promotion, and the family moved to the town of Gospic. In 1870, at the age of 14, Nikola Tesla, having completed his gymnasium education, moved to the town of Karlovac to enroll in a real school and study mathematics and foreign languages. He finished it in three years instead of the prescribed four. The teenager’s first major success, as he anticipated, went unnoticed by his parents. Young Tesla informed his father that he wanted to study to become an electrical engineer, although his father would have preferred his son to pursue a spiritual path. In the same year, a cholera epidemic broke out in Gospic, and the young man, infected with it, fell ill for a whole nine months. Doctors considered him hopeless, and in such a situation, his father promised to fulfill his son’s wish to become an engineer, only if he survived. And Nikola Tesla recovered. His father kept his promise and sent his son to the Austrian city of Graz to study at the higher technical school.

The First Idea

The educational institution where Nikola Tesla enrolled was renowned for its high-quality training in many technical disciplines. The young man enthusiastically immersed himself in his studies, not wasting a single hour of the day. In addition to the exact sciences, Tesla was passionate about foreign languages: upon entering the school, he already knew nine of them. Moreover, he had memorized books by authors such as William Shakespeare, Isaac Newton, and René Descartes. Despite Tesla’s successes, his teachers were concerned: the young man’s diligence bordered on obsession. Naturally, his classmates teased him. This hurt the young man, and he sought to distinguish himself in another way: he developed a penchant for gambling. Like in his other pursuits, Tesla knew no moderation and often lost substantial sums. When he won, much to the surprise of the card players, he always returned the money to the losers.

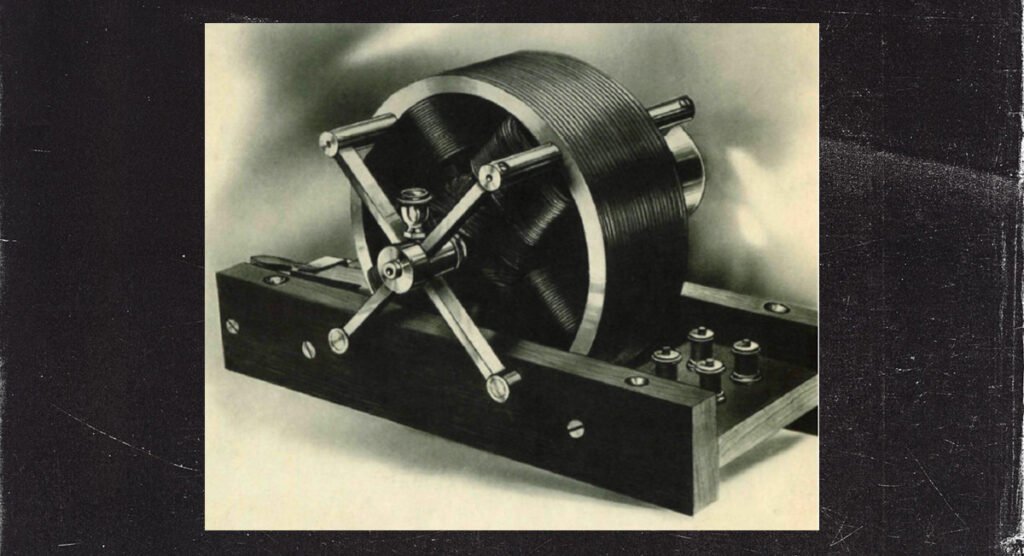

During his third year, Nikola Tesla became interested in what would later become his greatest practical discovery: the application of alternating current. One day, he told his professor that using direct current in the Gramme machine, an electric motor, was impractical. Tesla speculated that there was an “unnecessary” element in the mechanism — the commutator: without it, the current from direct would convert to alternating, and the device would operate more efficiently. The professor insisted that the motor couldn’t function without the commutator and lectured extensively on the impossibility of using alternating current for such a purpose. But Tesla remained convinced that his idea was feasible.

Restlessness

Disappointed by the professor’s response, Tesla abandoned his studies and spent day and night playing cards, losing large sums of money. Once, in order to help his son settle his debts, Tesla’s mother had to borrow money from friends. He managed to win back the money and repay his mother’s debt, but from then on, Nikola Tesla forever gave up playing cards.

Without completing his higher technical education, the young man found a job as an assistant engineer in the nearby city of Maribor. This job brought in a decent income, and Tesla was able to save money for further education. He didn’t give up on the idea of improving the electric motor and conducted physical experiments in his spare time.

Bookworm

To say that Nikola Tesla read a lot would be an understatement. He could recite entire volumes from memory, possessing what is now called “photographic memory.” His favorite authors included Shakespeare, Voltaire, Descartes, and Goethe. In his mature years, Tesla became interested in literature dedicated to Buddhism. He was drawn to this religious-philosophical system through his scientific work. Tesla once said: “In this world, there is not a single living creature, from man conquering the elements to the tiniest beings, that does not influence others. Whatever action is taken, no matter how insignificant, disturbs the cosmic balance, leading to the movement of the Universe.”

Great Revelation

In Intellectual Circles

The Tesla family was close-knit. Meeting with relatives, Nikola attended his father’s sermons in church and had friendly conversations with his mother and younger sisters. But in 1878, Milutin Tesla passed away. Feeling it was his duty to obtain a higher education, the younger Tesla enrolled in the Faculty of Natural Sciences at Charles University in Prague in 1880, one of the oldest institutions of higher education in Europe. Being in an intellectual environment became the best remedy for Tesla after losing his father. He enthusiastically studied physics, mathematics, and philosophy. During his studies, he became acquainted with the works of the Austrian physicist and positivist philosopher Ernst Mach, who was the rector of the university. However, due to financial difficulties, Tesla had to leave the university after just one semester and find work.

On the advice of acquaintances, he moved to Budapest and found a position as an electrical engineer at the Hungarian Telegraph Company. There, Tesla became familiar with the works of the American inventor Thomas Edison and the latest achievements in telephony at that time. He also made his first invention — a voice amplifier in the telephone apparatus, a precursor to the modern speaker. In his free time from work, Tesla often stayed late at the office to study the new equipment used in the company or worked on an idea that obsessed him — the alternating current motor.

Unusual Ability

Nikola Tesla possessed an extremely developed imaginative and spatial thinking ability, which allowed him to visualize any mechanism, drawing, structure, or mathematical equation. He could easily imagine the necessary object and see it in the smallest detail.

Working at the telephone company served as a source of inspiration for Tesla’s own experiments and improvements. Fully dedicating himself to his favorite activity, the young man minimized his rest time to about five hours a day, with no more than two to three hours allocated for sleep. This led to severe exhaustion and, consequently, to a rare nervous disorder characterized by heightened sensitivity of all sensory organs: the slightest sound was perceived as loud noise, and even a light touch caused excruciating pain. Doctors declared the young engineer terminally ill and predicted his imminent death.

Tesla refused to accept this verdict and, even while in a semi-daze, continued to work on his alternating current motor project. He felt that the solution was already in his mind, just waiting to be grasped. Several months later, contrary to all predictions, the illness receded, and shortly afterward, he found the solution to his problem. In his electric motor, Tesla applied what later became known as a rotating magnetic field. He was the first to use it to generate alternating current. In the early nineteenth century, the French physicist Dominique François Arago experimented with rotating a magnet using a copper disk. In 1881, engineer Marcel Deprez received an award at the World’s Fair in Paris for an experiment demonstrating that a motor could operate without a commutator: a similar idea was proposed by Tesla during his student years. However, Deprez’s innovative ideas were not realized due to insufficient development. Other scientists, such as Italian physicist Galileo Ferraris (1885) and American engineer Charles Bradley (1887), conducted experiments with a rotating magnetic field similar to Tesla’s. Both of them used alternating current transformers, which engineers John Gibbs and Lucien Gaul made in the mid-1880s, selling their invention to American George Westinghouse. Tesla would later maintain close business relations with Westinghouse.

However, Gibbs and Gaul’s transformer still had the commutator that Tesla wanted to eliminate. Later, upon learning about his Serbian colleague’s concept, Ferraris admitted: “Tesla’s developments are much deeper than mine.” Naturally, the abundance of similar developments raised the question of priority. The young inventor faced accusations of lack of originality and the “obviousness” of his discovery. Few immediately recognized the novelty of the new motor. London professor of physics Silvanus Thompson, one of the most original researchers of electricity of his time, wrote that Tesla surpassed his colleagues because he discovered “a new method of electrical power transmission.” Tesla himself believed: “I admit that rotating a motor, periodically changing the poles of one of the elements, is no longer new… In such cases, I use true alternating current, and my invention consists of discovering a model or method of using such a current.” Subsequently, the district court of the American state of Connecticut acknowledged that the first description of a motor operating on alternating current was indeed made by Tesla in his lecture at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in 1888, and that he created the first functional mechanism of this kind.

Pre-Electric Europe

During Tesla’s youth, the only means of generating electricity were water wheels installed in mountainous regions, such as in the Alps in southern France and northern Italy. The possibility of obtaining electricity was discovered just 25 years before the scientist’s birth when English physicist Michael Faraday discovered the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction in 1831. This allowed for the construction of the first electric motors, but electricity production remained very expensive, and there was no infrastructure for its transmission over long distances. People used candles and oil lamps for lighting and wood stoves for heating water. Electricity began to be more widely used in the 1880s, when the inventions of Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla’s future main competitor, became known in Europe. The efficiency of Edison’s generators, which operated on direct current, was extremely low, and they could only provide electricity to the largest cities in Europe. In provincial towns, electricity appeared only after Nikola Tesla developed alternating current motors. The wide application of the Serbian scientist’s discovery began several years after his departure from Europe.

Departure to the USA

Meeting with Edison

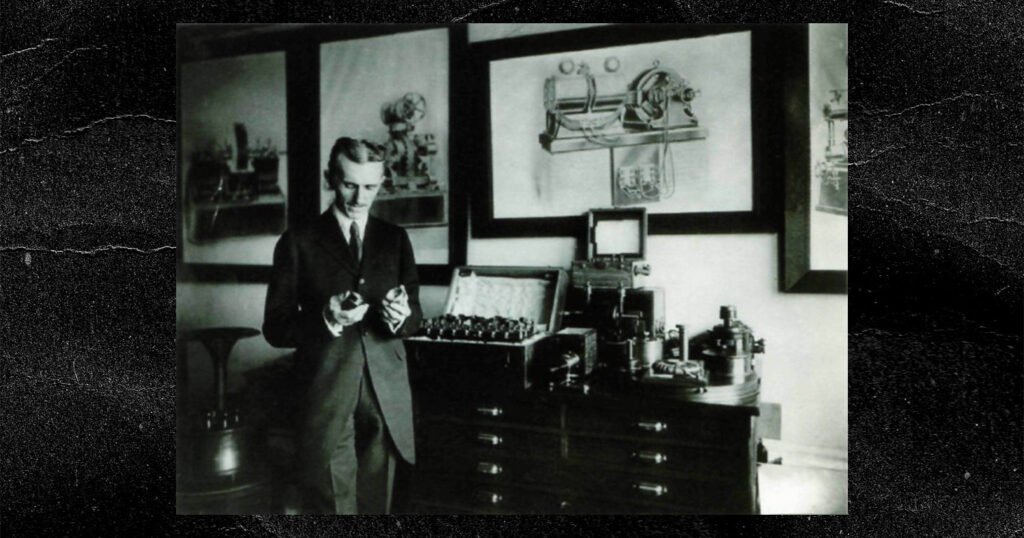

In April 1882, Tesla traveled to Paris to meet with representatives of the famous American inventor Thomas Edison. He hoped to find a sponsor to enable him to build his motor, which existed only on paper at that time. Tesla was particularly eager to meet Charles Batchelor, the manager of “Edison Continental.” Batchelor, nicknamed the “chief mechanic,” was born in England but moved to the USA in the 1870s to collaborate with Edison, becoming his right-hand man. After meeting with him, Tesla secured a job at “Edison Continental.” Settling in Paris, the inventor rose at five o’clock every morning, swam in the bathhouse before work, and after work met new acquaintances in the billiard room to discuss his motor project. In 1883, Tesla was sent to Strasbourg to establish a power station at the railway station being built there.

In addition to his main work, Tesla assembled a working model of an alternating current generator in his workshop. The first person Tesla presented his completed invention to was the mayor of Strasbourg, Baucen. He sympathized with the inventor and sought to find wealthy sponsors for him, but his efforts were unsuccessful. Having successfully completed his task, Tesla returned to Paris. Batchelor advised him to go to the USA to work directly at Edison’s enterprises. There is an unconfirmed version that in a letter to his boss, Batchelor wrote: “I know two great men: you are one of them, and the other is this young man.”

In the spring of 1884, Tesla went to New York. The “land of equal opportunities” initially made an extremely unfavorable impression on him. It all started with the fact that he was robbed. Moreover, compared to the refined grandeur of European cities, New York seemed rough and uncivilized to him. Tesla also had a very ambiguous view of his first meeting with Edison. From the very beginning, the difference in the characters of the two great inventors became apparent. Tesla had the refined manners typical of a European intellectual. Edison, on the other hand, asked him if he ate human flesh during their meeting. This was a hint that Tesla was born in the Balkans, meaning, according to Edison’s conception, not far from Transylvania, the “homeland” of Count Dracula. Tesla was struck by this coarse and primitive joke. Nevertheless, he felt a deep respect for a man who had achieved so much with minimal academic preparation. Our hero had spent a lot of time on education, hours sitting in libraries with books, knowing a dozen languages, and now he wondered: had he wasted his time on subjects that would not bring him any practical benefit? But later, Tesla realized that Edison’s trial-and-error method was not at all contrary to his own approach, which involved visualizing the problem beforehand.

Empty Promise

Although Edison did not approve of Tesla’s interest in alternating current, he recognized the Serbian’s undeniable talent in electrical engineering and hired the young man to work in his company, “Edison Machine Works,” assigning him to improve direct current generators. Thomas Edison was famous not only for his technical genius and all-conquering pragmatism — his main criterion in work was market testing — but also for his, shall we say, peculiar character. He had a habit of offering large bonuses to new employees but did not pay them upon completion of the work, thus obtaining a ready-made project practically for free. Tesla fell for this trap as well. Edison offered him $50,000 for improving direct current machines. However, when everything was ready — Tesla presented Edison with 24(!) variations of the mechanism — he laughed, saying, “You are still a Parisian. When you become a real American, you will appreciate this American joke.” Offended, Tesla bid farewell to Edison and decided to work independently.

Edison vs. Tesla

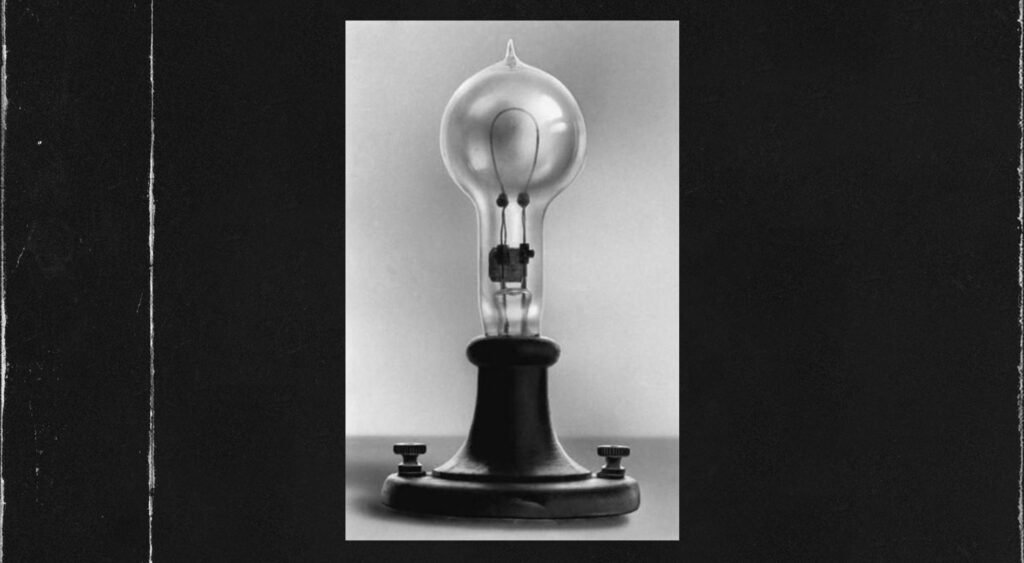

No inventor in the world can compare to Thomas Edison in productivity. His incandescent lamp remains the most common means of lighting human homes today. When Nikola Tesla met Edison in his New York laboratory in 1884, he already had the status of a living legend. The collaboration between the two great inventors did not last long. It would be difficult to find two more different people. Edison had a volatile and heavy character but was also a “go-getter.” Tesla, on the other hand, was a delicate introvert. The “Wizard of Menlo Park” (named after Edison’s laboratory in a small town in New Jersey) was characterized by his brusqueness: he could, for example, run current through a sink so that his subordinates “would listen better”! At the same time, he enjoyed inviting visitors to his laboratory and surprising them with various oddities—talking machines or lamps that colored darkness cherry red. Edison was friends with writers like Mark Twain and Stephen Crane, as well as journalist James Harper. Tesla also met them. Like many innovative engineers, Edison lacked the money to launch his products into production. This was especially true for his electrical projects. The direct current generators, which Edison relied on, turned out to be inefficient, and competitors surpassed him in developing more practical methods of power supply. In the end, the alternating current generators proposed by Nikola Tesla won. In the so-called “current wars,” Edison suffered defeat but still remained the most famous inventor in the world in the eyes of posterity.

Creative Independence

Tesla’s First Venture

Leaving “Edison Machine Works” in early 1885 due to the dishonesty of the great inventor, Tesla couldn’t help but appreciate the experience gained during his collaboration with Edison. Over three years of work at his enterprises, the engineer became acquainted with many American technical novelties of which he had no previous knowledge. At the end of the same year, Tesla founded his first enterprise, “Tesla Electric Light and Manufacturing.” His business thrived, and just a year later, the prominent electrical engineering journal “Electrical Review” dedicated the front page of its August 14 issue to Tesla’s company. The journal was published by Edison’s long-time rival, George Westinghouse, who soon began a direct collaboration with Tesla. However, it was too early to celebrate. Tesla registered the company with three people: himself and two entrepreneurs from New Jersey, B. A. Veil and Robert Lane, who acted as investors. They were interested in the engineer’s project to install a municipal system of arc lamps for street lighting in the town of Rahway, where Veil lived, but both investors remained indifferent to Tesla’s main creation, the alternating current generator. Moreover, they proved to be so unscrupulous that they forced the inventor to leave his own company. To make ends meet, Tesla had to take on any work, including digging ditches. He bitterly recalled later: “My education in various fields of science, mechanics, and literature seemed to me to be a mockery.”

But soon luck smiled again on the inventor. He met engineer Alfred Brown, who, interested in Tesla’s ideas, introduced him to lawyer Charles Peck. Peck had a good understanding of electrical engineering and was aware of the imperfections of direct current generators. Together, the three of them created a new enterprise, opening a laboratory located at 89 Liberty Street.

The next 15 years became the most productive period in Nikola Tesla’s life. Collaborating with Westinghouse, Tesla, working at the limit of human capabilities, quickly obtained patents for several alternating current devices. In the business world, a struggle began to cooperate with the holder of the rights to the most efficient alternating current system. Tesla had several competitors, the main ones being William Stanley, who worked on improving the apparatus of Golar Gibbs in George Westinghouse’s company, and Elihu Thomson of the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, a distinguished engineer who invented a system of alternating current that was largely similar to Tesla’s concept. The “decisive battle” between Thomson and Tesla took place at the famous lecture at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers in May 1888. There, the Serbian inventor presented his system, proving that it was capable of transmitting electrical energy hundreds of miles from its source, while his competitor’s project allowed electricity transmission only within a mile. Thomson, who had been working in the field of electrical engineering much longer than Tesla, was annoyed. Not wanting to concede primacy, he claimed that his invention was almost identical to his competitor’s project: the difference between them was only that he conducted experiments using a single, not double electrical circuit, but at the same time achieved a change in the direction of the current and the rotation of the magnetic field. But this was the crucial difference: the double circuit allowed Tesla to “get rid of” the commutator and thereby greatly increase the efficiency of his motor. Since Stanley also could not avoid using the commutator, Tesla became the author of the most advanced model of the alternating current motor. George Westinghouse, possessing excellent business acumen, realized that he needed to become a partner of the Serbian engineer as soon as possible. In July 1888, the entrepreneur invited Tesla to a meeting in Pittsburgh to discuss the acquisition of his patents. Mutual sympathy and trust arose immediately. The partnership proved to be mutually beneficial.

In 1887-1888, Westinghouse managed to increase the income of his company fourfold, and he was able to pay Tesla handsomely for the patents. It is difficult to determine the total amount received by the inventor from his partner, but it is known that from 1888 to 1897, it amounted to about 100 thousand dollars, in today’s currency it would be several million. In July 1888, Tesla left his home with a garden in New York and settled in one of the best hotels in Pittsburgh. Since then, until the end of his life, he preferred to live in hotels: it seemed more convenient to the engineer.

Chronology

Invention by Invention

In terms of fame, Nikola Tesla undoubtedly lags behind inventors like Thomas Edison or Alexander Bell. However, judging by the number of inventions and, most importantly, their prevalence, it turns out that social memory has been unfair to Tesla. The availability of inexpensive electricity in homes and industries is owed to the work of the engineer in creating the alternating current generator and transmission system. The radio that we listen to at home or on the way to work was created in part thanks to Tesla’s work. Modern mobile phones and the Internet emerged as a result of research into wireless energy transmission, pioneered by Tesla. Life was not always kind to this man, and after his death, his name became surrounded by a network of legends where truth is sometimes difficult to distinguish from fiction.

Inventions, Discoveries, and Improvements

- Induction motor 1877

- Alternating current motor 1883

- Multiphase alternating current system 1888

- Arc lamp lighting system 1891

- Tesla coil 1891

- Wireless energy transmission (Tesla effect) 1891

- Wireless communication; radio 1893

- Remote control 1898

- Bladeless turbine 1913

“War of Currents”

Edison’s Provocation

Tesla’s motor revolutionized the transmission of electrical power. The “war of currents” began. In December 1888, Thomas Edison invited engineer Harold Brown to his laboratory to conduct joint research on the application of alternating current. To discredit Tesla and Westinghouse, their main competitor suggested using alternating current to execute criminals, presenting his idea as “the most humane and painless execution.” The first person lawfully sent to the afterlife by electricity was a certain William Kemmler, convicted of murdering Westinghouse’s lover. Tesla and Westinghouse failed to prevent this gruesome experiment. The first execution in the electric chair was unsuccessful: Kemmler did not die after the first 17-second shock but suffered severe burns. The execution was deemed barbaric by those present. Brown was blamed for the failure to perfect the “most humane execution” mechanism. However, Edison achieved his main goal: public opinion began to view alternating current with apprehension. Work on Tesla’s system had to be suspended as sponsors categorically refused to finance it.

Despite the losses, Westinghouse remained confident in the prospects of Tesla’s projects. In 1891, he obtained permission to resume the development and testing of the new technology. “A slight burn, but nothing more.” After a short trip to Paris for the World’s Fair, Tesla returned to New York to open a new laboratory there. It occupied the entire fourth floor of a building on Fifth Avenue. There, the engineer began to study the relationship between electricity and sound waves. Tesla came to the idea of the Earth’s inexhaustible resources and pondered the problem of using them to generate electricity. He believed that the Earth’s atmosphere was filled with a special substance, ether, through which energy could be transmitted with minimal losses. The engineer’s main technical interest became its wireless transmission. Tesla believed that in the future, this would change the very method of energy management.

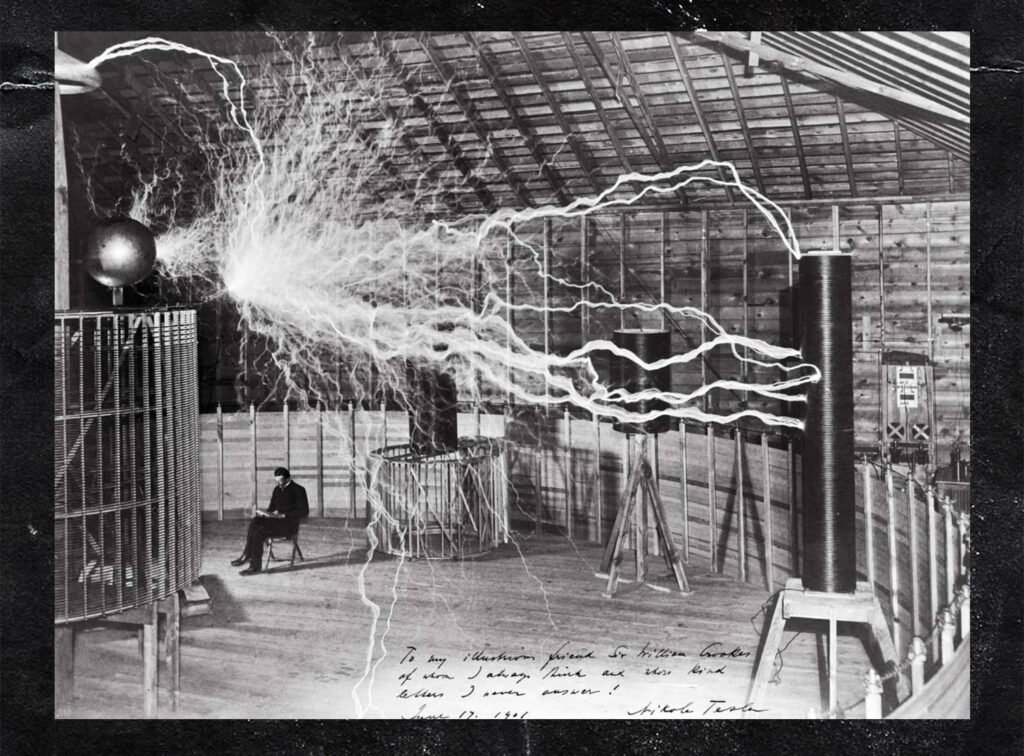

From 1889 to 1891, Tesla regularly met with his friend Thomas Martin, a writer and engineer, telling him about his projects. In 1890, Martin dedicated a whole spread in the Electrical World magazine to the scientist, which was good publicity for the inventor. Around the same time, Tesla began risky experiments: he passed through his own body discharges of enormous voltage. The high frequency made them relatively harmless. He demonstrated his experiments to an audience: during his performance, light bulbs in Tesla’s hands lit up. When someone asked about the pain of such a process, the engineer replied, “Sometimes I get a slight burn, but nothing more.” The value of such experiments also lay in the fact that for them, the scientist developed rules that formed the basis of modern safety techniques.

Spectacular Experiment

At the end of 1891, Nikola Tesla received news of his mother’s illness. He immediately went to Gospic, where he found her bedridden. In April 1892, the scientist’s mother passed away. From grief, the right temple of her son temporarily turned gray. For a month and a half after the funeral, Tesla stayed in Gospic with his relatives. This became one of the longest breaks in work that he allowed himself. In February 1893, Tesla, together with Martin, went to the National Electric Light Association Congress in St. Louis. The inventor demonstrated to the audience several of his works, including the multiphase alternating current system designed for power transmission. It was then that he first showed the public the “Tesla coil” – a transformer creating electrical oscillations that could be used for remote control. The discharges produced by the transformer looked very spectacular – like lightning discharges. According to him, he used a voltage of 300,000 volts, which would lead to immediate death if used differently. Such a colorful presentation could not fail to attract public attention to Tesla, which partly helped the inventor finally obtain American citizenship. From that moment on, the inventor’s personality began to be surrounded by fantastic legends.

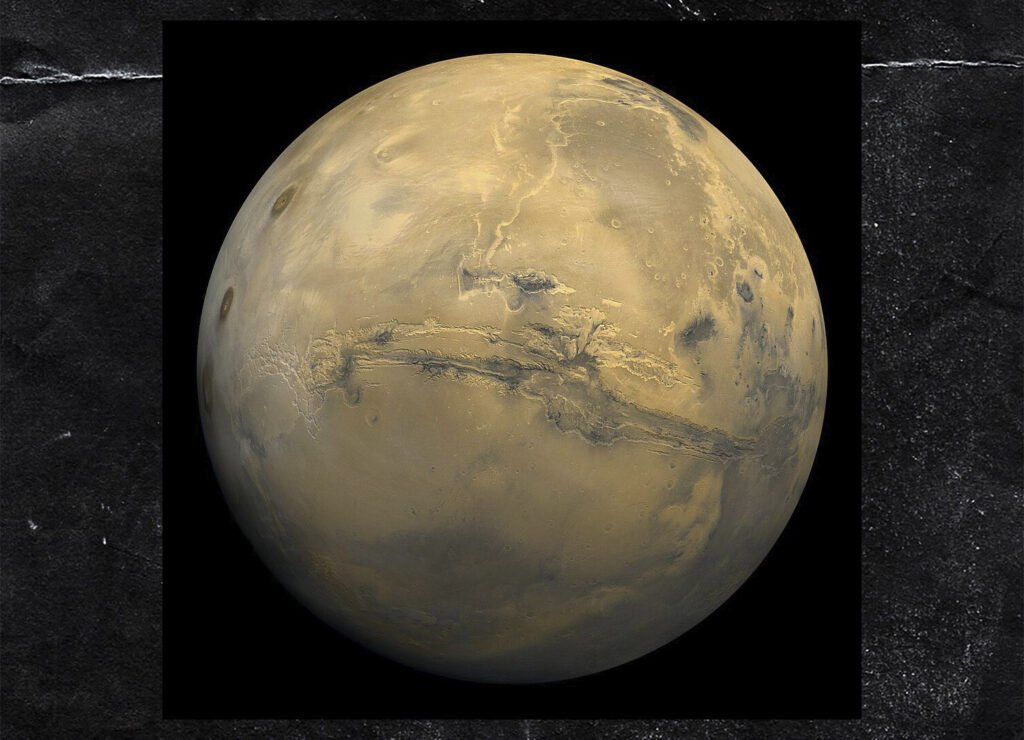

TESLA AND SCIENCE FICTION

Nikola Tesla’s experiments with the transformer – when flashes of electricity of remarkable strength and beauty flickered over his head – stirred the public’s imagination. Soon, the inventor began to transform into a character of science fiction. The mysterious and dramatic aura surrounding him was fostered by both the scientist’s peculiar behavior and his complex fate. But most importantly, it was his inventions and projects that seemed unimaginable. Many of Tesla’s ideas have become part of modern science fiction and fantasy genres. For example, it was he who proposed the idea of ray weapons, now present in almost every video game. Sometimes, in computer games, the killing of enemies is suggested to be carried out using discharges from Tesla’s transformer. Perhaps the scientist would have been very surprised to see such creations, indicating a layman’s perception of his legacy. The famous science fiction writer H.G. Wells drew inspiration from Tesla’s works, creating the novel “The First Men in the Moon” in 1901. There, even the scientist’s name is mentioned: “The reader will of course remember the interest aroused at the beginning of the new century by the announcement of Mr. Nikola Tesla, the famous American electrician, that he had received a message from Mars.”

Tesla’s idea of flying devices shaped like saucers – a precursor to the famous “flying saucers” – also became a classic of science fiction. A vast number of Tesla’s concepts remained on paper. Even today, some of them seem incredible.

Triumph

Let There Be Light in Chicago!

In 1893, George Westinghouse won the contract to provide lighting for the World’s Fair in Chicago. This was a significant success for him, as Edison’s “anti-advertising” had hurt his financial position. Westinghouse immediately turned to Tesla for help, and he agreed. To fulfill the order, the entrepreneur could not use incandescent lamps, as Edison did not grant him a license for their production. However, Westinghouse had access to another patent, albeit less efficient. This contract was very important for the company, as it promised huge revenue both directly and potentially. Tesla personally set up the lighting system and ensured Westinghouse’s enormous success.

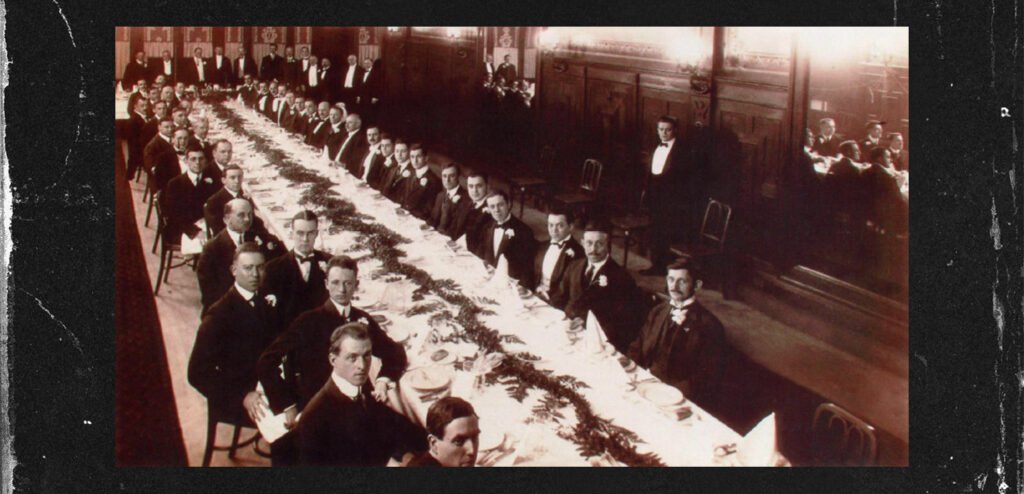

The exhibition opened on May 1, 1893. The total area of all exhibits was about 280 hectares. About 60 thousand participants worked at the fair, and its cost was around 25 million US dollars. “The White City” was visited by 28 million people. One of the most vivid impressions of the fair for the public was the lighting, made up of a quarter of a million working wireless lamps. They consumed three times more energy than was needed to illuminate the entire city of Chicago. This project, along with the experiments and inventions demonstrated at the fair, brought Tesla immense fame. In the press, he was called “the second Edison.”

In 1894, Thomas Martin introduced Tesla to Robert Johnson, the deputy editor of the magazine “Century.” This person became his closest friend. Johnson and his wife Catherine admired the personality and talents of the inventor, considering him almost a deity. The couple moved in the highest circles of New York society and were well acquainted with people like writer Mark Twain and US President Grover Cleveland. Remarkable people, they not only sincerely became interested in Tesla’s projects but also befriended him. This family became almost like family to the scientist. He loved inviting them to his laboratory for, as he put it, “surprises.” Especially for Robert Johnson, Tesla translated several Serbian poems into English.

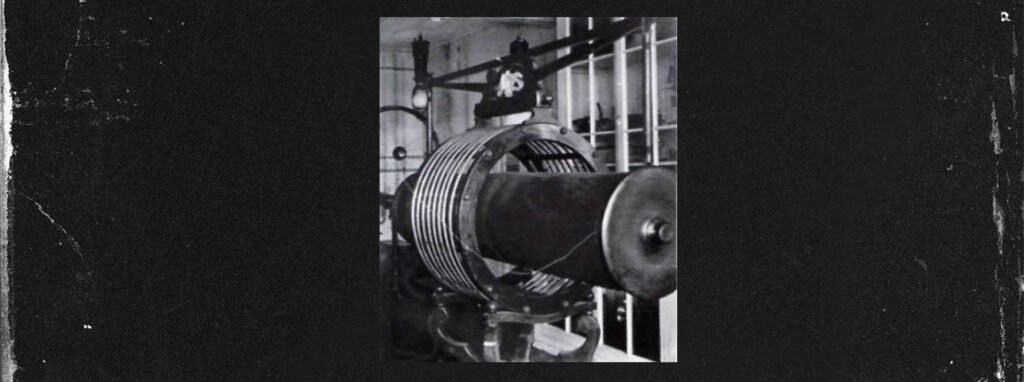

In 1894, Tesla was tasked with implementing the “Niagara project” to build the world’s first hydroelectric power station. It was the first serious test of his multi-phase alternating current system: it was necessary to provide electricity to the city of Buffalo, located 32 kilometers from the waterfall. This idea was put forward in the late 1880s by Thomas Edison, but at that time, there was no way to implement it because his direct current systems did not allow energy transmission over distances longer than a mile. To carry out such an ambitious project, it was possible to enlist the support of multimillionaire John Morgan. Initially, he supported Edison’s company, but in the 1890s, considering alternating current more promising, he “switched sides” to Westinghouse’s camp. The project lasted three years. In 1895, Tesla established a new company, becoming one of its directors, along with several prominent entrepreneurs.

In 1896, the Niagara Power Plant was opened, and Tesla’s multi-phase system made the world’s first long-distance power transmission. Thanks to cooperation with Westinghouse and Morgan, Tesla gained access to the highest echelons of the business elite. This allowed him to secure the necessary funding for his projects.

Version: Communication with Mars

In the late 1890s, scientists were captivated by the idea of contacting extraterrestrial civilizations. The discovery of remote energy transmission – Tesla’s effect – made it possible to assume the possibility of sending and receiving messages using wireless communication devices. Nikola Tesla pondered the possibility of contacting “Martians.” The scientific community began seriously hypothesizing about the inhabitants of the “red planet.” Many speculated that they were more advanced in their development than humans and had long overcome their animal instincts. In the 1896 article “Is it true that Tesla is planning to signal the stars?” the engineer stated that one of the goals of his research was to establish contact with extraterrestrials. After moving to Colorado Springs and setting up a huge laboratory there, Tesla came to believe that he was indeed receiving signals from Mars. He claimed that they were fundamentally different from storm noises and other sounds characteristic of Earth. It is impossible to determine exactly what led Tesla to such a misconception. Perhaps the engineer mistakenly interpreted some side effect of the new equipment as signals from space. Communication with Mars remains fiction to this day, but the engineer said, “The same principle can successfully be applied to transmitting news to any corner of the planet. It is possible to cover every city on the globe. Thus, a message sent from New York will reach England, Africa, and Australia in a split second.” Nowadays, such communications have become everyday reality.

Unfinished Projects

In Colorado Springs

In March 1895, Tesla experienced a major misfortune. His laboratory caught fire, destroying everything inside. The damage was estimated at around $250,000. The saddest part was that many papers and experimental samples were impossible to restore. Nevertheless, by September 1897, Tesla had already filed a patent application for his first wireless transmission invention. In 1899, the engineer moved from New York to Colorado Springs, Colorado. He chose this city because of its geographical location, which offered excellent opportunities for experiments with wireless energy transmission and the study of electrical storms.

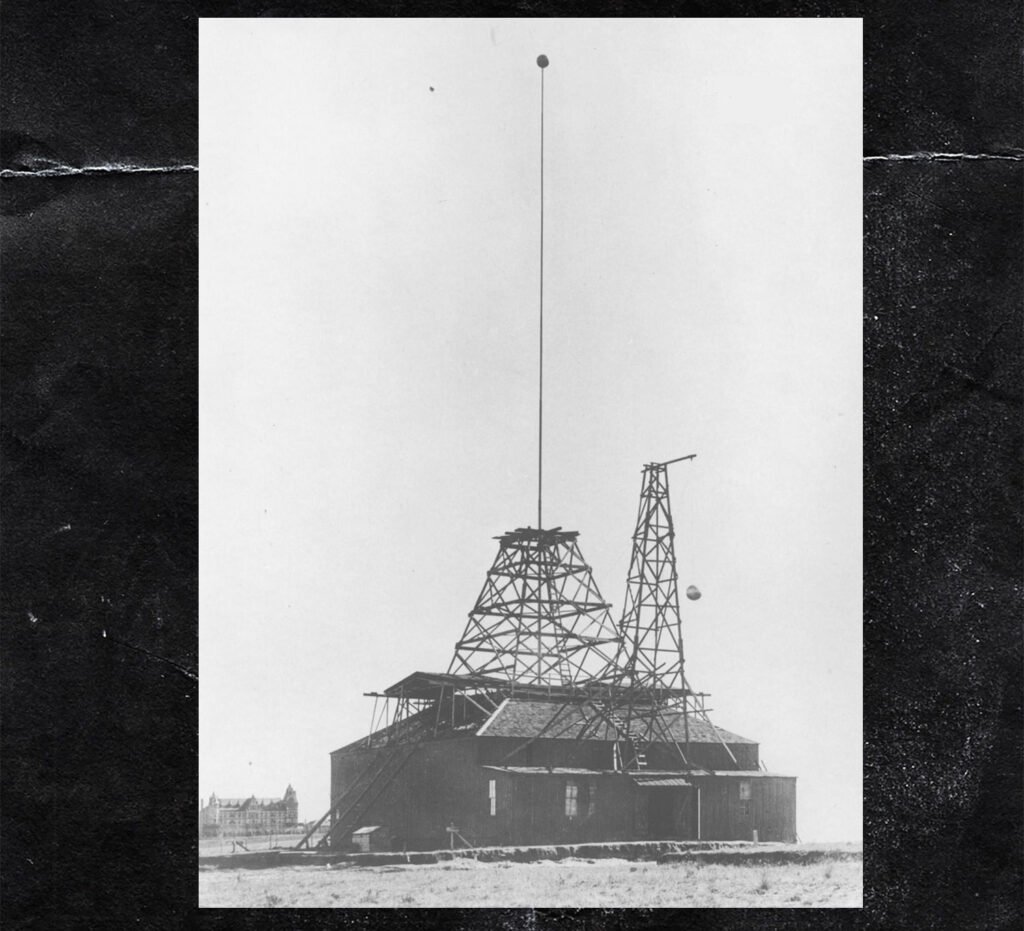

The Unfinished Tower

In January 1900, Nikola Tesla returned to New York. His finances were depleted, and he could no longer maintain the laboratory in Colorado Springs. Soon, he managed to find a new patron. John Morgan, who believed in Tesla’s genius, agreed to finance his project. In 1901, Nikola Tesla began work on the “Wardenclyffe Project” — the construction of a World Telegraphy Station that would be used for commercial purposes and generate significant profit. The engineer planned to build an entire city around the tower and turn it into the radio technology capital of the world. However, instead, Tesla, suspecting that Italian Guglielmo Marconi, who had obtained a patent in 1896 for one of the first devices for transmitting and receiving radio signals, was using his work, unilaterally changed the original plan and began constructing a huge tower, which he wanted to make the basis of a global wireless energy transmission system. Morgan’s generosity immediately waned: Tesla’s demands seemed excessive to him. Moreover, the entrepreneur did not want to tolerate insubordination. When Morgan learned that the scientist’s ultimate goal was to provide free electricity to the entire world, he considered him insane and cut off financial support.

Tesla, believing that his project would help bring electricity to every home on Earth, invested tens of thousands of his own savings into it. Despite all the difficulties, the tower was completed in 1902. This unique skeletal structure, built mostly of wood, stood until 1917 but was never used as its creator intended.

The Oddities of a Genius

Subsequent Years

In the subsequent years, Tesla engaged in tireless activities, about which little is known, leading to many speculations. He supposedly worked on creating “death rays” and an “impenetrable shield,” projects inspired by World War I and its aftermath. Nikola Tesla was always considered, to put it mildly, an eccentric. Having suffered from cholera in his youth, he developed a lifelong obsession with cleanliness. Fearing germs and contagious diseases, Tesla avoided handshakes. The great electrical engineer was also not a stranger to superstitions: for some reason, he tried to do everything in threes and would only stay in hotel rooms divisible by three. His strange habits, combined with his unusual worldview—he rejected Einstein’s theory of relativity, advocating instead for the concept of ether as a material substance, and believed in the existence of Martians—gave Tesla the reputation of a “mad genius.” His main rival, Thomas Edison, gained greater recognition partly because, unlike Tesla, he appeared “normal.” Formal accolades were few and far between for Tesla.

Recognition and Legacy

In 1916, Nikola Tesla received the Edison Medal, named after his rival, for his scientific achievements. In 1931, to mark his 75th birthday, Time magazine featured his portrait on the cover. When Tesla died alone in a hotel room on January 7, 1943, at the age of 83, two thousand people attended his funeral. After a service at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, his body was cremated.

FBI and Tesla’s Papers

In his final years, Nikola Tesla was working on the development of powerful weaponry. After his death, all his records were immediately confiscated by the FBI. With World War II underway, the government feared that documents outlining fundamentally new weapons could fall into the wrong hands. It is now impossible to determine exactly what was contained in the inventor’s notes. The FBI claimed it only found diaries with Tesla’s philosophical musings, but the public remained skeptical. According to one popular version, Tesla was designing an “impenetrable shield”—an electromagnetic field that would make a military base invulnerable to enemy attacks. Tesla had mentioned the idea of electromagnetic protection as early as 1915. Another well-known theory suggests that the engineer created some kind of “death ray” weapon, as he spoke of such an invention multiple times in his later years.

The Era of Electricity

The widespread use of electricity, which is indispensable to modern civilization, became possible thanks to the inventions and discoveries of Nikola Tesla. However, the designs of the “inventor of the 20th century” were aimed at a more distant future…

Electrification of the Entire Planet

There is no denying that the use of electricity plays a key role in the functioning of modern society. While we know that our ancestors managed without sockets and wires, we ourselves can hardly imagine life without electricity. The first reliably recorded observations of electricity were made by the ancient Egyptians. Five thousand years ago, they discovered this natural phenomenon by observing electric eels living in the Nile.

However, the first serious studies in this field date back only to the early 17th century, when the English physicist William Gilbert began studying static electricity, which arises from the friction of an amber plate. He also coined the term for this phenomenon from the ancient Greek word “electrikus,” meaning “amber.” In the 19th century, it was discovered that electricity could be controlled. This field of knowledge proved very promising not only for theoretical but also for practical research. It was electricity that enabled the rapid scientific and technical progress of the second half of the 19th century. The most significant pioneers in the practical use of electricity were Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse. By proving the principle of energy transportation, they managed to deliver current over a distance of a mile (1.61 kilometers), but the charge would then be lost. The reason was that the motors developed at that time operated on direct current. Nikola Tesla was the first to realize that with alternating current — which in its natural state is always alternating — it would be much easier (and thus cheaper) to transmit electrical charge over long distances. However, controlling alternating current was more difficult, and the first electric motors operated on direct current. Therefore, Tesla’s idea, proposed in the 1880s, sounded completely fantastic. Additionally, Edison actively promoted the idea that alternating current was much more dangerous than direct current.

A New Era

Edison did not mistakenly see Nikola Tesla as a dangerous competitor. Ultimately, it was Tesla’s project that spread not only in the United States but around the world, sending direct current generators into history. A few days after the Niagara Hydroelectric Power Plant was put into operation, a hydroelectric station in the Croatian village of Jaruga on the Krka River, Tesla’s homeland, became the first European enterprise of its kind. Transmission systems allowed homes and factories hundreds of kilometers from the power source to be supplied with electricity. Unsurprisingly, electricity supply quickly spread across the planet. Initially, systems for the production and consumption of electricity appeared in the most developed countries — the USA and Western Europe, but gradually there was not a single country left in the world that did not know electricity. However, even today, 1.6 billion people live without access to this form of energy.

Through Space

The legacy of Nikola Tesla is not limited to alternating current generators and hydroelectric power plants. The scientist’s research in the field of wireless signal transmission has played a huge role in shaping the face of modern society. As early as the 1820s, the movement of electric charge in a magnetic field was discovered. In his experiments in this field, Nikola Tesla primarily relied on the works of Michael Faraday and Heinrich Hertz on electromagnetism. At the same time, the “inventor of the 20th century” supported the 19th-century theory that the space of our world is formed by a special substance, imperceptible to human perception, called ether. Tesla believed that understanding the connection between electrical phenomena and this substance forming space would allow people to transmit not only radio waves but also any other information, such as images. Moreover, according to Tesla’s ideas, such “transmissions” would be possible not only within the boundaries of our planet’s space but also beyond it.

Boundless Innovation

Tesla was a genius in many fields of physics. Perhaps he can be called the most versatile inventor of all time. His area of activity—working with X-rays, vacuum tubes, radiation, and cosmic rays—was much broader than the interests of his main rivals, Edison and Marconi.

The engineer’s developments in remote control, robotics, radar technologies, and lasers made an enormous contribution to scientific and technical progress. Tesla’s last patent, registered in early 1928, was for a vertical take-off airplane, another testament to the breadth of his engineering thinking. The scientist’s works published in 1931 proposed a system for extracting energy by generating electricity through temperature fluctuations in the world’s oceans. Fascinated by Tesla’s grandiosity and research boldness, many researchers of his work attributed to him the most fantastic experiments, ranging from causing earthquakes to the fall of the Tunguska meteorite.

A World Illuminated by Electricity

The Potential of Electricity

Nikola Tesla once said, “We should determine the Earth’s electrical capacity and its electrical charge.”

The first country to experience the industrial revolution in the late 18th century was England. In other European countries, a similar technical breakthrough occurred during the 19th century, bringing about massive social changes. By the end of that century, the transmission of energy over long distances became possible, and electricity reached many remote corners of Europe. This was precisely what Nikola Tesla dreamed of when he was a student in Graz and Prague.

For many years, he worked on a generator capable of making electricity cheap and widely accessible. Thanks to Tesla, the process of electrification began, leading to the abandonment of traditional methods of energy production and radically transforming the appearance of cities and villages. The introduction of new technologies meant not only the construction of power plants but also the extensive infrastructure necessary for their operation. Where a new power plant appeared, an entire city grew around it. In the United States, mass electrification led to the creation of the Rural Electrification Administration in 1935 as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program. This agency, under the Department of Agriculture, supported the work of local electric and telephone companies. Similar institutions appeared in other countries worldwide. The introduction of electricity into agriculture significantly reduced and eased human labor. It was used for various purposes, such as electric pumps for drawing water from wells, eliminating the need for manual labor. Food preservation became much easier with electric refrigerators. Electric lighting opened new possibilities for society in the evenings. These examples are endless and all testify to the enormous impact Tesla’s method of energy supply had on humanity.

Electric Transport

One of the manifestations of electrification was the emergence of new types of transportation. Steam and diesel locomotives were converted to electric. This sharply reduced environmental pollution created by a single train, even when the power station operated on burning coal. Additionally, electric trains moved faster and required less technical maintenance. They produced less noise than steam or diesel locomotives, making it possible to use electric trains for urban transportation with frequent stops. Long-distance trains also benefited from such conversions. Today, it is hard to imagine that none of this might have existed if Edison had succeeded in suppressing Tesla’s projects. Nowadays, almost all trains in Europe, from subways to long-distance trains, run on electric power. Transportation means like trolleybuses and trams help reduce environmental pollution in densely populated urban areas. The idea of electrifying cars also seems logical. In the late 1990s, the first models of cars running partially on gasoline and partially on electricity appeared. One reason for this is their lower performance compared to “traditional” cars. Their batteries need recharging after a few hours of driving, and considering the pace of modern life, such a “luxury” is not affordable for everyone. However, as Tesla foresaw, the need for alternative energy sources is growing as the world’s oil reserves are depleting. It seems we are on the verge of another industrial revolution when humanity will be able to completely abandon oil and petroleum products, discovering new sources of electricity.

The Charm of Talent

Throughout his life, Nikola Tesla encountered various people—both enthusiasts ready to offer their support and detractors. Despite his eccentric habits, Nikola Tesla knew how to be a good friend to those who appreciated his colossal work and the innovation in his projects.

Business Partner

George Westinghouse (1846–1914)

George Westinghouse, Nikola Tesla’s closest business partner and long-time rival of Thomas Edison, was a pioneer in the electrical industry. He realized early on that the capabilities of Edison’s direct current systems were limited and sought a more economically advantageous means of producing and transmitting energy. In the early 1880s, he acquired the rights to Tesla’s system for generating and transmitting alternating current. This was a bold move, as no significant trials of the young engineer’s work had yet taken place. But Westinghouse immediately believed in Tesla. The risk paid off: the entrepreneur and the inventor defeated Edison in the so-called “War of Currents,” successfully illuminated the Chicago World’s Fair, and secured a contract to build the Niagara Hydroelectric Power Plant, whose energy supplies to Buffalo in 1896 marked the world’s first long-distance transmission of electricity. Subsequently, Westinghouse worked on implementing Tesla’s alternating current system in various states across America.

Westinghouse himself was also an inventor of several innovations. At 19, he created a rotary steam engine, and at 22, he developed a pneumatic braking system. His projects to improve railway signaling sparked his interest in electrical engineering. His entrepreneurial instincts led Westinghouse to focus on this industrial sector. By hiring Nikola Tesla into his company, Westinghouse gave the inventor the opportunity to bring some of his most grandiose ideas to life. Westinghouse not only made significant money from this but also etched his name into the history of the electrical industry. George Westinghouse passed away in 1914 at the age of 67.

Physicist and Positivist Philosopher

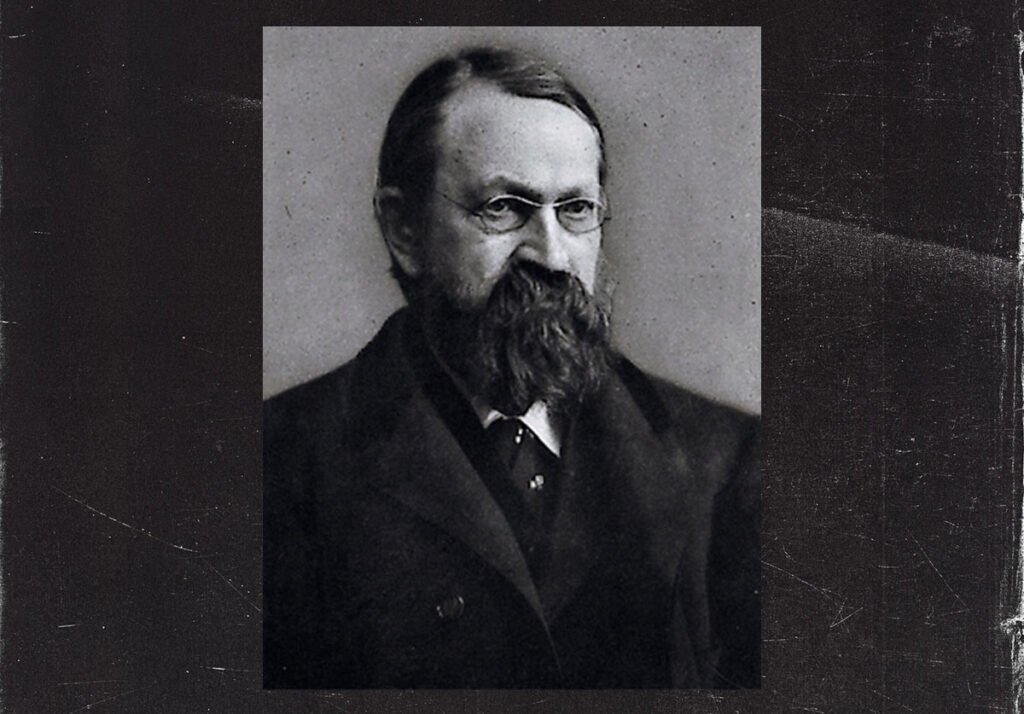

Ernst Mach (1838–1916)

Researchers of Tesla’s work often attribute great significance to Ernst Mach in shaping the views of the great Serbian inventor, even though there are no direct references to Mach in Tesla’s writings. Their attention was drawn to the similarity between Mach’s concept of the “thought experiment,” which later became a fundamental tool of theoretical physics, and Nikola Tesla’s practice of creating mental images. Tesla was able to not only accurately reproduce but also conduct tests on his inventions in his imagination. According to Tesla, the machines he brought to life always—without a single exception—behaved exactly as they did during his “thought experiments.” However, this unique ability of the genius inventor had nothing to do with the abstract speculations proposed by theoretical physicists, such as imagining falling into a black hole in an elevator. Unlike such abstract speculations, Tesla’s mental images were seen by him in the most literal sense. This trait of his personality could not have manifested simply from reading Mach’s works, although Tesla, as a student of the Faculty of Natural Philosophy at the University of Prague, was undoubtedly familiar with them.

The renowned physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach is best known for his research on shock waves and his positivist approach to the general problems of natural science. Mach studied at the University of Vienna, and in 1867 he received the chair of experimental physics at the Charles University in Prague, where he remained a professor for 28 years. In 1879, a year before Tesla arrived in Prague, he was appointed the university’s rector. In 1895, Mach returned to teach at his alma mater. He died at his son’s home in Munich, a day after his 78th birthday.

Devoted Admirer

Katherine Johnson (d. 1925)

Katherine Johnson was the wife of journalist and editor Robert Johnson. Little is known about her personal life except for her friendship with Nikola Tesla. For many years, Johnson was a sincere admirer of Tesla’s work, and in the 1890s in New York, she often accompanied him to official events or simply to dinners at restaurants. She enjoyed boasting about Tesla to her friends. The relationship between them could be described as a platonic romance. Katherine Johnson was a faithful wife to her husband, whom the great scientist considered one of his few confidants. However, despite her devotion to her lawful spouse, she held much greater respect for the inventor due to his unconventional views.

Tesla, although never married—believing that abstinence heightened mental faculties—felt a strong attraction to her strong and egocentric personality. Katherine Johnson became something of a personal psychologist, best friend, and surrogate mother to him. She noticed when the scientist appeared tired—immersed in his work, he could easily forget to eat—and made sure he gave his body at least a little rest. Katherine Johnson and Nikola Tesla exchanged a vast number of letters throughout their lives, and in almost every one, she inquired about his health and mood. Tesla loved the Johnsons’ children, Owen and Agnes, as if they were his own. The scientist bitterly mourned Katherine Johnson’s sudden death in 1925.

The greatest American writer of the 19th century

Mark Twain (1835—1910)

Mark Twain is one of the most distinctive writers in the United States, earning the title of “father of American literature.” He was born into a family of a Florida salesman. His early childhood was tough: out of six siblings, only three survived into adulthood. The town of Hannibal on the Mississippi River, where the family later moved, later became the prototype of St. Petersburg in his famous books “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” The writer was interested in scientific research and science fiction literature, and throughout his life maintained a friendly relationship with Nikola Tesla. Mark Twain passed away in 1910 at the age of 75.

Mark Twain and Nikola Tesla met in the 1890s when the engineer, famous for his bold projects, began circulating in New York’s high society. Tesla, who had admired Mark Twain’s books since childhood, told him during their meeting how, during a severe illness in his youth, the works of this remarkable writer sustained his will to live. The inventor often invited Mark Twain to his laboratory, and once, using experimental fluorescent lamps, took his photograph. Later, journalist Thomas Martin published it as an illustration for one of his articles about the great scientist. A few days before his death, Tesla sent a courier with an envelope to “Mr. Samuel Clemens,” that is, Mark Twain. The courier soon returned, reporting that the named street, Fifth Avenue, no longer existed. Tesla instructed the courier to go back and not return without giving the envelope to the money-needing Mark Twain, who allegedly visited him the night before… Apparently, by the end of his life, Tesla ceased to distinguish his inner world from the external world.

Famous financier

John Morgan (1837-1913)

Tesla once said, “Morgan towered above all the financiers of Wall Street, like Samson over the Philistines.” Impressed by Tesla’s success in constructing the Niagara Falls hydroelectric power station, Morgan became interested in the scientist’s developments and agreed to sponsor the “Wardenclyffe project.” He provided $150,000 for the construction of a tower on Long Island, New York. However, soon after signing the contract, the relationship between the financier and the engineer soured. Due to manipulations in the railroad industry, in which Morgan was involved, a collapse occurred in the stock market. The entrepreneur began to lose interest in the project. Upon learning that after the tower was erected, Tesla planned to provide the world with free electricity, Morgan ceased financing and even started dissuading other potential investors from dealing with Tesla. American banker and financier John Morgan was one of the richest men of his time. He had a tough character, and apparently, it required considerable courage from Tesla to negotiate money inflows with him. On the other hand, the financier was also a well-known collector, and he viewed the engineer’s work as a form of art – apparently, this helped him maintain interest in Tesla’s fantastical projects for quite some time. By the way, Morgan should have been thankful to Tesla for the fact that the clairvoyant strongly advised him to refrain from traveling on the Titanic, which sank during its maiden transatlantic voyage on April 15, 1912.

Author of the first patent for the invention of radio

Guglielmo Marconi (1874—1937)

The clash with Guglielmo Marconi was one of the most unpleasant experiences in Nikola Tesla’s life. The Italian, based on the developments of Heinrich Hertz and Oliver Lodge, constructed his own radio device and patented it in 1897. In 1900, he visited the United States and expressed a desire to familiarize himself with Tesla’s work. In 1901, Marconi successfully transmitted a radio signal across the Atlantic Ocean. Tesla, who had achieved a similar result as early as 1891, using an original method, suspected that Marconi had unlawfully used his developments. He decided to create a worldwide wireless communication system through the “Wardenclyffe project” and thereby “deal with” Marconi. Subsequently, all of this led to a lengthy dispute over the priority of the invention of the radio between him and Marconi, and essentially between the United States and Italy. In 1943, the year of Tesla’s death and several years after Marconi’s death, the US Supreme Court recognized the priority of the Serbian scientist, who had become an American citizen. In reality, the invention of the radio in its modern form included a whole chain of innovations, in which singling out one singular achievement of either scientist would be incorrect. Guglielmo Marconi has gone down in history as one of the developers of the radiotelegraph system: his company, bringing together many talented engineers, made significant progress in creating radio technology as an independent specialty. In 1909, Marconi received the Nobel Prize for this. Guglielmo Marconi, in the 1920s becoming a staunch fascist, was involved in the leadership of the fascist party and died in 1937 in Rome from a heart attack.

Nikola Tesla’s legacy

Over his long life, Nikola Tesla did a lot to change the world and improve people’s lives. We owe many of our everyday things to this scientist. His ideas, which seemed fantastic to his contemporaries, are being realized today.

Mobile world

Throughout his life, Nikola Tesla carried the conviction that electricity should become accessible to all people on Earth, and he tirelessly worked to make this a reality. His developments and experiments laid the foundation for the creation of many devices not only in electrical engineering but also in modern telecommunications. Wireless transmission of information proved to be a very promising field. In 1920, less than 30 years after Tesla successfully sent the first radio signal, the world’s first news broadcast took place. Soon, television also became a reality. After the initial successful experiments, it rapidly grew into a whole industry. Today, wireless energy transmission is commonplace. It is thanks to this principle that portable radios, mobile phones, the Internet, and satellite television, which have become commonplace, operate. Although many of Nikola Tesla’s ideas have been realized, attitudes toward him remain somewhat ambiguous.

Two Teslas

There are two main perspectives on the creative work of Nikola Tesla: the “mystical” and the skeptical. Supporters of the mystical view believe that Tesla’s recognized contributions to electrical engineering are just the tip of the iceberg. They argue that Tesla achieved his main breakthroughs in the second half of his life when he engaged in global research on extracting electrical energy from the Earth and its practical use in the military sphere, such as creating an “unbreakable shield” – a high-power electromagnetic field capable of closing the borders of states from foreign invasion, as well as “death rays” intended to strike enemy targets with tremendous force. Tesla allegedly even conducted a successful experiment of this kind: the so-called Tunguska meteorite, which caused huge destruction in the area of the Podkamennaya Tunguska River on June 30, 1908, was supposedly his doing. Later, realizing his responsibility if such deadly weapons fell into the hands of unscrupulous politicians, Tesla preferred to suspend and then destroy the fruits of his work. The fact that his archive immediately fell into the hands of the FBI after his death and remains inaccessible to scientists indirectly confirms this.

From the perspective of opponents, this proves nothing. The materials available to researchers only suggest more or less successful futuristic predictions by Nikola Tesla, but nothing more. There are no constructive texts proving, for example, that he specifically developed the principles of the Internet. There are only general discussions of this kind. However, besides Tesla, there are other people known for foreseeing future technical discoveries, such as the French writer Jules Verne. The tragedy of Tesla, according to modern scientists, lies in the fact that he exceeded his competence: while Tesla acted as an electrical engineer, he achieved great feats that truly transformed modern civilization. However, when this extraordinary man took on the role of a physicist and thinker, he suffered a setback, leading him to create mystifications. Tesla began to work for the public: all his “electrical experiments” and loud statements aimed to raise funds for his imagination-striking, but alas, fantastical projects. He never admitted to this. Apparently, the most reasonable position in this dispute is to take an intermediate position. Just because modern science cannot reproduce Tesla’s experiments does not mean that future science will not be able to, or that they are inherently irreproducible. However, blindly insisting that Tesla, who was not inclined to distinguish between mental and real, physical types of experiments, was always right in everything, is also not prudent. The line between truth and self-deception in such cases is very thin and dangerous.

What will happen next?

Thus, the question of Nikola Tesla’s legacy remains open. Many of his ideas are still awaiting verification and, possibly, realization. Modern engineers continue to search for more efficient ways to harness energy from sunlight, wind, seawater, and even from outer space: the need to conserve our planet’s natural resources is becoming increasingly urgent. Tesla emphasized the need for thrift over a hundred years ago, when the issue of depleting the Earth’s crust was not as acute. Perhaps this prudent attitude is related to the scientist’s religious beliefs: he admitted to being a deeply religious person at heart. It is known that in addition to Christian theology, Tesla read a lot of Eastern literature. Perhaps from there he derived the sense of interconnectedness of all processes happening on Earth and the fragility of the pervasive harmony in the world. Familiarity with the basic concepts of Nikola Tesla is part of the mandatory curriculum for anyone studying electrical engineering. Many leading universities in the United States, such as the University of California, Berkeley, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pay special attention to the engineer’s legacy. His works are actively studied in his homeland – Serbia and Croatia. Nevertheless, Nikola Tesla’s ideas and projects will remain at the forefront of researchers’ attention for a long time to come.